In an effort to bring the noise attenuation ratings of hearing protectors more in line with real-world usage, the EPA has recently announced a proposed change the Noise Reduction Rating.

It has long been known that many workers in the "real world" do not achieve the same level of attenuation from hearing protectors as indicated on the EPA required Noise Reduction Rating (NRR) label. This problem is so widely accepted that OSHA recommends de-rating NRRs by 50%. But other studies have shown that a one size-fits-all de-rating is also inaccurate and can cause problems of overprotection. It is this situation the EPA is attempting to rectify.

Under the new scheme, the use of the acronym NRR will be retained, but it will now represent a “range" as opposed to a single-digit "rating." The proposed method is still likely to use standardized and controlled testing to show the capability of a given hearing protector, but the new NRR is expected to provide an indication of how much attenuation trained users (the lower number) versus highly motivated trained users (the higher number) can be expected to achieve.

While the new method is expected to be more accurate than the current system, some complain that it will gain accuracy at the expense of simplicity. Where safety managers used of have a single number to deal with, they will now have to contend with two, or possibly three, depending on how much weight is given the lab test rating. Many are already asking how they are supposed to use the added information, and whether complicating the rating will actually help.

Looking at the Numbers

Any time an average or median (the most commonly occurring number in a range of numbers) or other "one-number" descriptor is used, you only get part of the story. For example, for a given car, the average fuel economy may be "labeled" at 22 miles/gallon, but the range, depending on driving conditions, driver habits, grade of fuel, load in the vehicle, etc., may vary from 16–25, or it may range from 21-23. That range tells you a lot more information for that vehicle than the single number provides. If the range is narrow, you can infer that as all those variables change, the fuel economy is stable. If the range is wide, you don't know which conditions change the result, but you do know that one or more does highly influence the outcome.

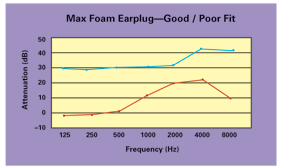

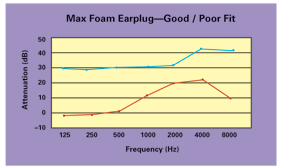

In the case of hearing protectors, both the low and the high end of the EPA's proposed attenuation range are based on trained users. The word, "trained," is important here. Studies show (see Figure 1) that naïve or "untrained" users get much less attenuation from earplugs than trained users. Studies of real world attenuation also show (see Figure 2) that workers tend to fall into two categories. They either fit the hearing protector well (+ or –5 dB of the published NRR) or very poorly (less than 10 dB of attenuation).

| Attenuation achieved by a good fit versus poor fit of a foam earplug in a worker's ear. A poor acoustic seal causes no attenuation of hazardous low-frequency noise, and little attenuation in high frequencies. |

| Figure 1. |

| Recent studies of real world attenuation show workers tend to either fit the hearing protector well (+ or –5 dB of the published NRR) or very poorly (less than 10 dB of attenuation). The chart shows field attenuation of 104 workers. Data collected at eight facilities in 2007 by the Howard Leight Acoustical Lab, San Diego, CA..

|

| Figure 2. |

Which Number to Use?

The conservative approach would be to use the lower of the numbers in the range. For most workers in the United States, daily time-weighted exposure levels are less than 95 dBA. In these cases, attenuation of 10-15 dB is adequate to lower the daily exposure to a safe level. Generally, exposures are variable throughout the day, but the damage risk criteria are based on daily exposures with auditory rest between exposures. Keeping the overall level throughout the day below 85 dB, or to be safer, 80 dB, is the goal.

However, use of the lower attenuation number can also increase the risk of overprotection in certain situations. Say, for example, that a worker exposed to 90 dBA of noise uses a hearing protector with the range of 12-30 dB of attenuation. If that worker can consistently achieve a fit that provides 30 dB or more of attenuation, he or she is protected down to 60 dB. At this level the worker may not be able to hear important signals (warning beeps, etc.), especially if the worker has some level of hearing loss. In many work environments, such a level of overprotection could be positively dangerous.

For high intensity noise environments, use of the lower attenuation number may also limit the available selection of hearing protectors.

Assessing Fit

The key, then, is to know how much attenuation hearing protectors are actually providing, regardless of their stated range. Physical factors such as material composition and shape can influence the attenuation level of an earplug. But the fit of the hearing protector is the primary factor in determining how much attenuation it provides. And "fit" is totally under the control of the user, though many users don't know what a good fit sounds like.

That's where fit testing systems can help. Fit testing can help to train workers to consistently attain higher attenuation levels, and more importantly, it can provide a closer match between the levels of hazard and protection.

There are several types of fit testing systems now on the market that provide feedback to the individual. VeriPRO® from Howard Leight® makes it possible for safety managers to ensure employees are getting the most out of their hearing protection devices. VeriPRO uses subjective testing to measure real-world attenuation of the worker's own, unmodified earplugs, and can be used as a means to improve individual employee training and enhance the overall effectiveness of hearing conservation programs.

Systems like VeriPRO benefit both safety managers and employees alike. For the safety manager, they fulfill OSHA's requirements for training with documented results. For employees, they demonstrate the importance of hearing protection in the workplace, and help them learn how to achieve the best results from their hearing protectors.

More importantly, subjective fit testing takes the guesswork out of the hearing protector selection process. Rather than worry about which range or rating number to use and whether workers are sufficiently protected in their noise environment, fit testing allows selection to be based on the only really significant number: the actual level of protection a particular worker achieves with his or her actual earplugs in his actual work environment.